Dancing (In)Equity

by Yayoi Kambara

I feel my face getting hot and I realize I’m starting to sweat. Self-introductions always freak me out. Everyone else sounds so articulate and thoughtful about their creative practice and artistic histories. I look around the conference table and wonder if I’m having a major bout of impostor syndrome. I look over at Gerald Casel, who gives me encouraging looks with his warm eyes and slow, calm nods as I begin. I get some positive hmms and snaps from group members after I finish. All of a sudden I realize: I belong here in this cohort, Dancing Around Race. In fact, I really need to be here.

I felt honored and intrigued when Hope Mohr invited me to participate in Gerald Casel’s Dancing Around Race cohort, so I quickly signed on board. Mohr's Bridge Project is supporting choreographer Casel and a cohort of artists for a full year through its Community Engagement Residency. Members of the artist cohort for Dancing Around Race are: Raissa Simpson, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Sammay Dizon, David Herrera and myself. Our group is meeting monthly for a year to engage in discussions about the intersection of race and the performing arts. We’ve invited critics, curators, funders, designers, and scholars to join our conversation. A key line of inquiry for the year is how to make creative practices and cultural institutions more equitable.

So, what is equity? To say defining and tackling this question as a group has been challenging and mind-blowing for me as an individual would be an understatement. One of the most powerful discussions regarding (in)equity to emerge in Dancing Around Race so far has centered on the colonized body. My body is colonized. My body has been colonized by white aesthetics. I don’t think I could have said those words aloud and fully understood them until this summer. I was born in Japan, my family emigrated to California when I was seven, we then moved to England for four years, and since the age of sixteen I’ve spent my life back in the US. I’m a person of color who grew up as a third culture kid and didn’t even know I was a person of color until I lived outside of Japan.

For me, the colonization of my body comes from the fact that I’ve mainly trained in European dance forms, and I was ushered along in my dance training and career because I had a certain body: thin, athletic, able-bodied, with a facility for movement. Although one can argue that dancers willingly sign up to have their bodies choreographed on and scrutinized, no one prepared me for the implications of this colonization. I feel at odds with the constraints of white aesthetics because I have felt that inside of these constraints, I didn’t belong. Perhaps my third culture upbringing manifested itself in my ability to creatively problem solve and integrate other aesthetics while still preserving my Japanese identity. Having felt tokenized as a dancer, as a choreographer I am now looking to have a seat at the creative table. Although I'm incredibly grateful to and cognizant of the amazingly talented choreographers I've had the pleasure of working with and learning from, I think it's fair to say that the artistic leadership in contemporary dance is predominantly white.

Another aspect of (in)equity in dance that I’ve become more aware of this year has been the impact of my racial identity on how my work receives funding. One of the advisory board members for my company, KAMBARA + DANCERS, who has followed my work for years recently asked me why I wasn’t creating something “simply gorgeous,” particularly in these troubling times when people might appreciate a respite from the news. I replied that I haven’t received funding for my work unless social commentary is involved. Instead, I’ve only received funding so far for work tied to my racial identity. For example, one of my dances is a reflection on the Japanese-American Internment and its current relevance. This work received funding. In contrast, another work I recently wanted to make that was not explicitly related to my racial identity didn’t.

If artists of color only receive funding for conceptual work related to their racial self-identity, it denies artists of color opportunities for expression. For me, this granting trend implies that only my race matters in evaluating and funding my art. This trend also implies that if artists of color create dance for dance's sake, it has less value than the works that white choreographers are allowed and commissioned to create. In their attempt to promote equity by funding identity-driven dance, funding sources reinforce racial boundaries. Just because my racial identity informs my person and my work, does that mean that all my funded creative expression needs to be somehow related to my skin color?

I rarely hear white choreographers articulating their diasporic history, defined as any group migration from a region or country, or evaluate their ethno-racial backgrounds in relation to their work. While they may have a diasporic history themselves, their privilege or ‘whiteness’ in dance translates into a freedom simply to make work. Funders, curators, and the press relate to their work as choreographers without requiring an added lens. I’ve noticed when qualitative discussion or critique occurs around the white choreographers by grant panels or the press, we often hear about form, choreographic craft, physical architecture and the experience from the viewer’s perspective. As artists of color, we have to self-identify and explain ourselves in relationship to the work we make, particularly in concert dance. In our current funding structure, our work is discussed with a narrative that includes self-identity and how it’s embedded in work. Is it equitable to have different systems to critique and potentially fund work? Is there a future when artists of color don’t have to explain themselves or is this just a reality not only of our field, but our lives in the U. S.?

The freedom to dream is our best creative habit. As such, in my upcoming curatorship for the Asian Art Museum’s Thursday Nights Program, I’m asking local self-identifying Asian artists to create outside the constraints of aesthetic cues that are generally stated in project grant proposals. In our current dance funding system, artists of color are rarely afforded this luxury. Institutional support that isn’t earmarked for a specific project can liberate artists and validate our creativity.

Along with my participation in Dancing Around Race this year, I was invited to be a 2018-20 fellow in the APAP Leadership Fellows Program (LFP), an international cohort of 25 administrators, artists, and curators looking at equity and how performing arts organizations define and implement equity in our practices. My involvement in these ongoing conversations has prompted me to update my company's core values. During the APAP LFP intensive, choreographers Liz Lerman and Marc Bamuthi Joseph defined the categories that any arts organization must consider: Aesthetics, Community/Social Values, Organizational Health and Personal Responsibility. As a choreographer, the aesthetics category concerns me the most. How do I value a dance as good, beautiful and true?

I’ve realized that I cannot discuss aesthetics without discussing (in)equity, particularly when it comes to race, as one piece or kind of art cannot represent everyone’s experiences. Can I be trusted to build work that embodies my definitions around (in)equity, whether it is pure dance or conceptually driven work around my identity and community?

If the three pillars of equity are Access, Power, and Representation, how do we ensure all audiences have access to and engage with art that they want to see? Ken Foster, who co-directs APAP LFP with Krista Bradley, stated that “art is life.” What he means is that art exists within a web of socio-economic ecosystems. As in any ecosystem, adaptability and resilience are necessary to survive, particularly in the arts. From this, I understand that the consumer-oriented transactional basis for the patronage and consumption of the arts must change. In order for there to be equitable access to the arts, we need to reinvent the ticketing structure. For KAMBARA + DANCERS, I’ve made a commitment to offer a sliding scale for tickets to all events. I want my supporters to know that they have access, the power of choice, and they represent with their presence at the event. They choose which pricing tier bests suits their wallets. I like to believe that this gives the audience a sense of agency in its relationship with the arts. Another way to change the hierarchy of ticket pricing is to not tier tickets, so there are no VIP tickets and seats. Shouldn’t all audience members be VIPs?

Another key area where financial (in)equity must be addressed is in regards to dancer pay. We’re all aware that Bay Area cities are some of the most expensive cities in the country. But sadly, many emerging and even established choreographers pay their dancers a stipend or an hourly rate well below minimum wage. Perhaps choreographers have experienced this themselves as dancers and thus believe it to be an equitable practice. However, it’s exploitative and mainly those dancers who have other means of financial support can participate in the creative process. Also, how do we justify paying the lighting designers, production managers, and tech crew more than the dancers? I value all the talent needed to make a production come to life, but aren't dancers at the core of our work? Can we, directors and choreographers, commit to paying an equitable hourly rate at or above the minimum wage?

In May, the Dancing Around Race cohort met with a group of funders: Margot Melcon from the Zellerbach Family Foundation, Ted Russell from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation and Barbara Mumby from the Arts Commission. We asked each of them how their organizations were addressing equity. Russell discussed the role of white patriarchy at the root of inequity and how in the US, racism is built into the very structure of our country. He commented, “If you can move the needle on race, you move the needle on everything else. If you don’t mention race, it’s very easy to leave it out because of the deep discomfort around the issue.” In my opinion, some arts organizations make sweeping statements regarding diversity and inclusion, thereby shutting down the possibility of real discourse. Our “deep discomfort” with these topics prevents any real action. Unless we directly address race when we discuss inequities, we’re doing nothing to move this needle.

In July, I was a student in Nicole Klaymoon’s Embodiment Project’s summer intensive Get FREE. The Get FREE Workshop is a Hip Hop Dance Festival and intensive rooted in cultural preservation, tradition, and community. And the whole week was completely cost-free. Every teacher was deliberate and intentional about the roots of the movement language and dances, and we participated in daily panel discussions addressing equity. The classes also stressed non-verbal ways of learning and nonhierarchical ways of warming up. This intentionality about street dance and its roots in Black/African American culture further liberated me from the white aesthetic of concert dance. And I literally sweated aesthetic ideas out of my colonized body. I felt free.

Dancers might be some of the most open-minded people, but we all have biases to address. We must continue to update our equity lens in order to bring our performing arts field forward. In our April meeting for Dancing Around Race, artist Julie Tolentino stressed that we need to uplift one another as we confront racial inequity in dance. Let’s commit to doing so.

Special thanks to my family, dance colleagues, company dancers, the dancers I sweated with and on during the Get FREE workshop, and the APAP Leadership Fellows Program. And a super loud shout-out of deep gratitude to my invaluable Dancing Around Race cohort group.

Yayoi Kambara performed with ODC/Dance from 2003–2015 and has danced with numerous Bay Area companies. The founding of KAMBARA + DANCERS in 2015 was a big year of transition from performer to choreographer. Kambara’s choreography credits include Opera Parallèle (Little Prince) and the Center for Contemporary Opera (Gordon Getty’s Scare Pair). She has been commissioned by Mardi Gras with Garrison Keillor at Nourse Auditorium, and Yerba Buena Gardens Festival Choreofest.

The next Dancing Around Race public event is Thursday, September 20th at Humanist Hall in Oakland at 7 PM. Featuring guest speaker Aruna D'Souza, author of Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in Three Acts. FREE to the public, but reservations are required: https://www.artful.ly/store/events/15335

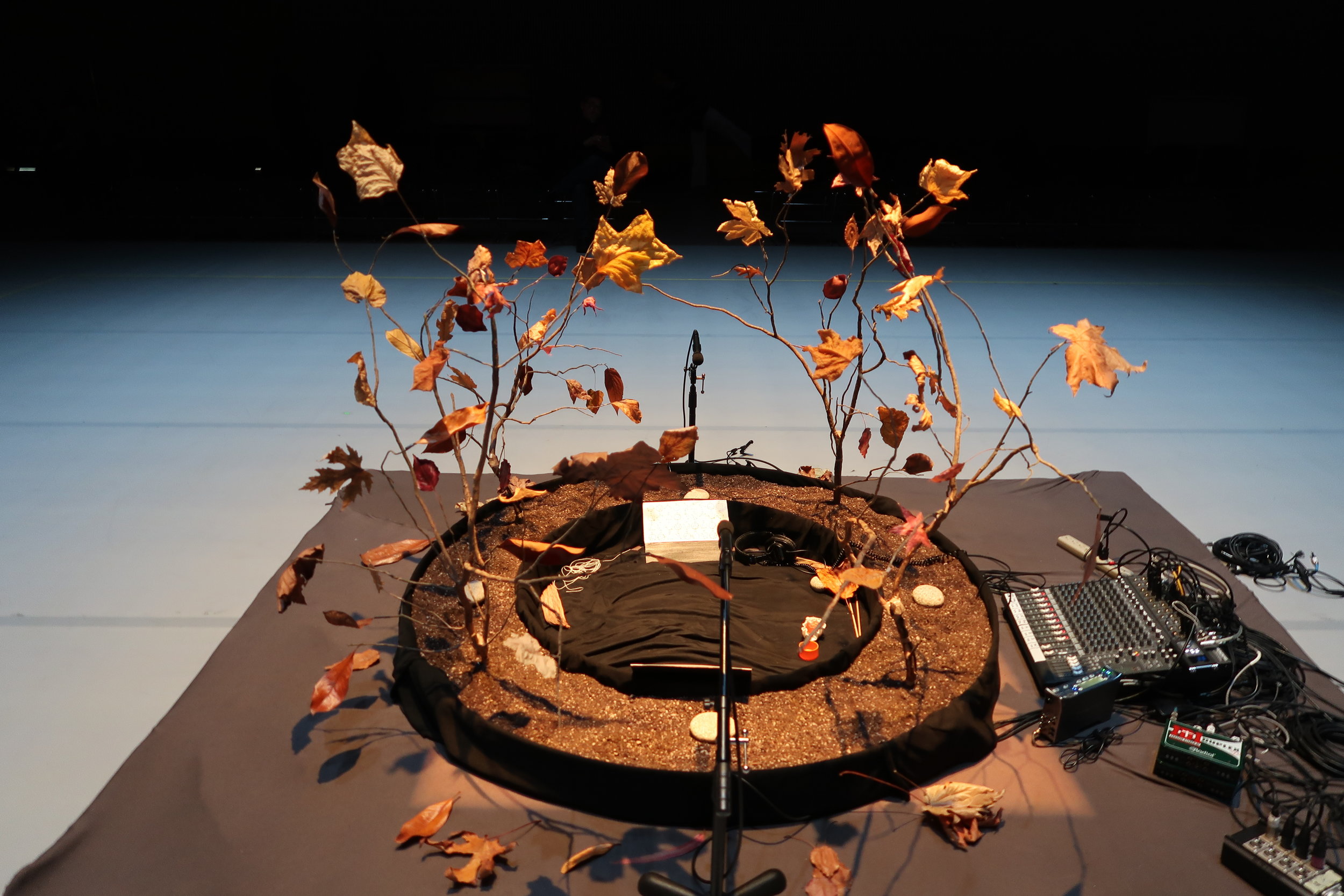

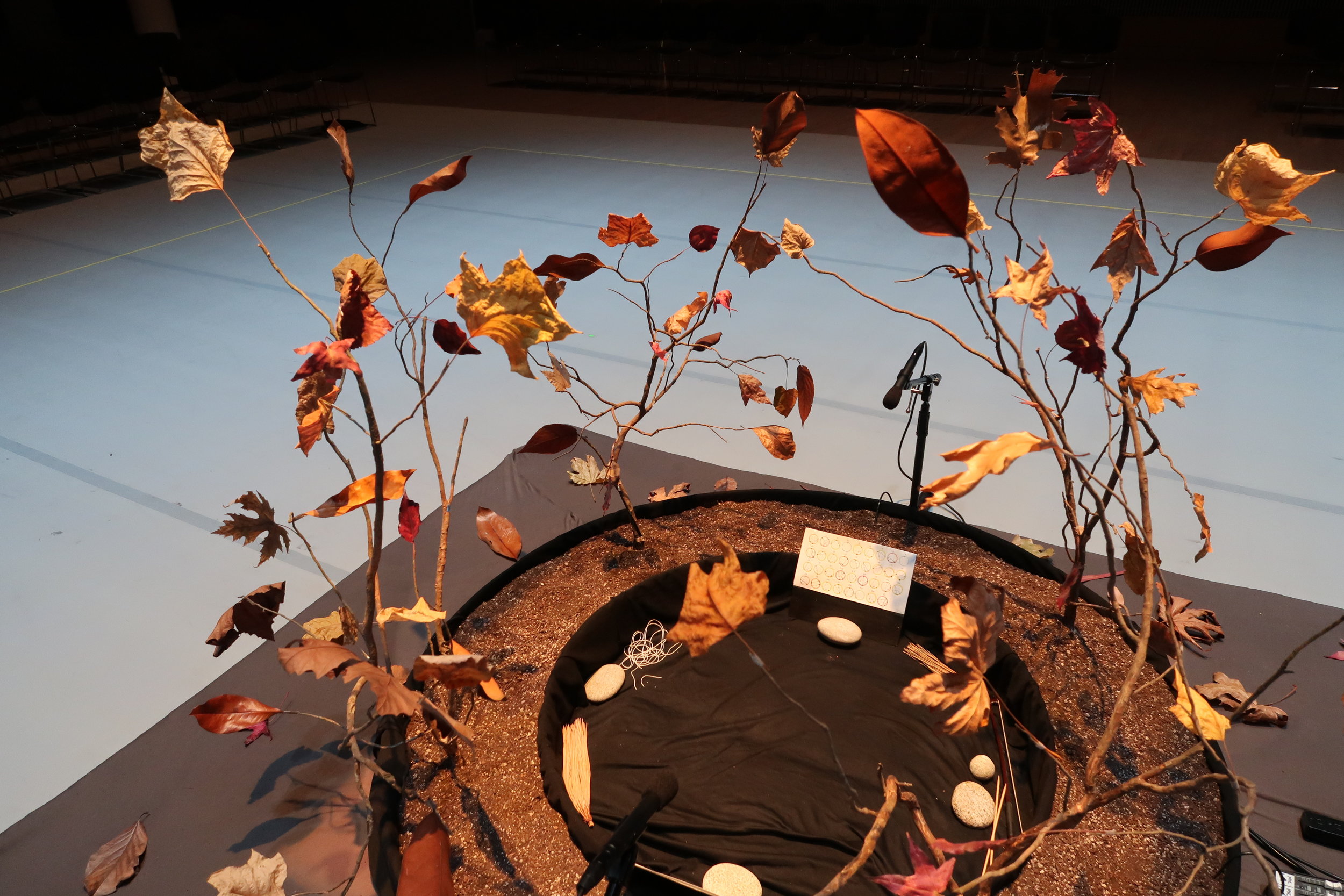

Photo: Yayoi Kambara at one of the Dancing Around Race cohort meetings.

![Photo by Margo Moritz of Peiling Kao in per[mute]ing.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/550a1c94e4b0545b6579edde/1477607327334-3OY2APVMU9UTFRDXX43I/HopeMohr_1055.jpg)

![Photo by Margo Moritz of Peiling Kao and Tracy Taylor Grubbs in per[mute]ing.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/550a1c94e4b0545b6579edde/1477607360021-J4Z2B3ZU92F3F0HBYX2O/HopeMohr_1081.jpg)

![Photo by Cheryl Leonard of Grubbs and Kao in rehearsal for per[mute]ing.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/550a1c94e4b0545b6579edde/1477612226356-745DX3CKHE4TNBHZJ0A2/image-asset.jpeg)